This must-see exhibit showcases work by one of the greatest photographers of the 20th century

When Vivian Maier died in 2009 at the age of 83, a short obituary in the Chicago Tribune identified her as a “photographer extraordinaire” but left it at that. Her photographs had never reached the mainstream; in fact, much of her work remained undeveloped.

By chance, artist John Maloof stumbled up on a box of her negatives at an auction house and eventually realized there was something special about them. He shared the images with photographers and gallerists, and eventually Vivian Maier’s work started getting the attention it deserved. At last, Maier is now considered one of the greatest photographers of the 20th century, and you can see her evidence of that in “Unseen Work,” an incredible new show at Fotografiska in the Flatiron District through September 29.

RECOMMENDED: Fotografiska is officially moving from its Flatiron address

The Fotografiska show is the first major retrospective of Maier’s work in the U.S., and it’s packed with 230 photographs and video clips that explore the late artist’s extraordinary talent. The images range from the early 1950s to the late 1990s, documenting post-war America and the facade of the American dream.

Maier was born in the Bronx in 1926 to a French mother and an Austrian father, then spent her early years between New York and France where she started trying photography in the late 1940s. In 1951, she returned to New York City to work as a governess, then continued that career in Chicago’s suburbs starting in 1956. While caring for several children, she found time for her passion in photography, sometimes capturing childhood through her lens.

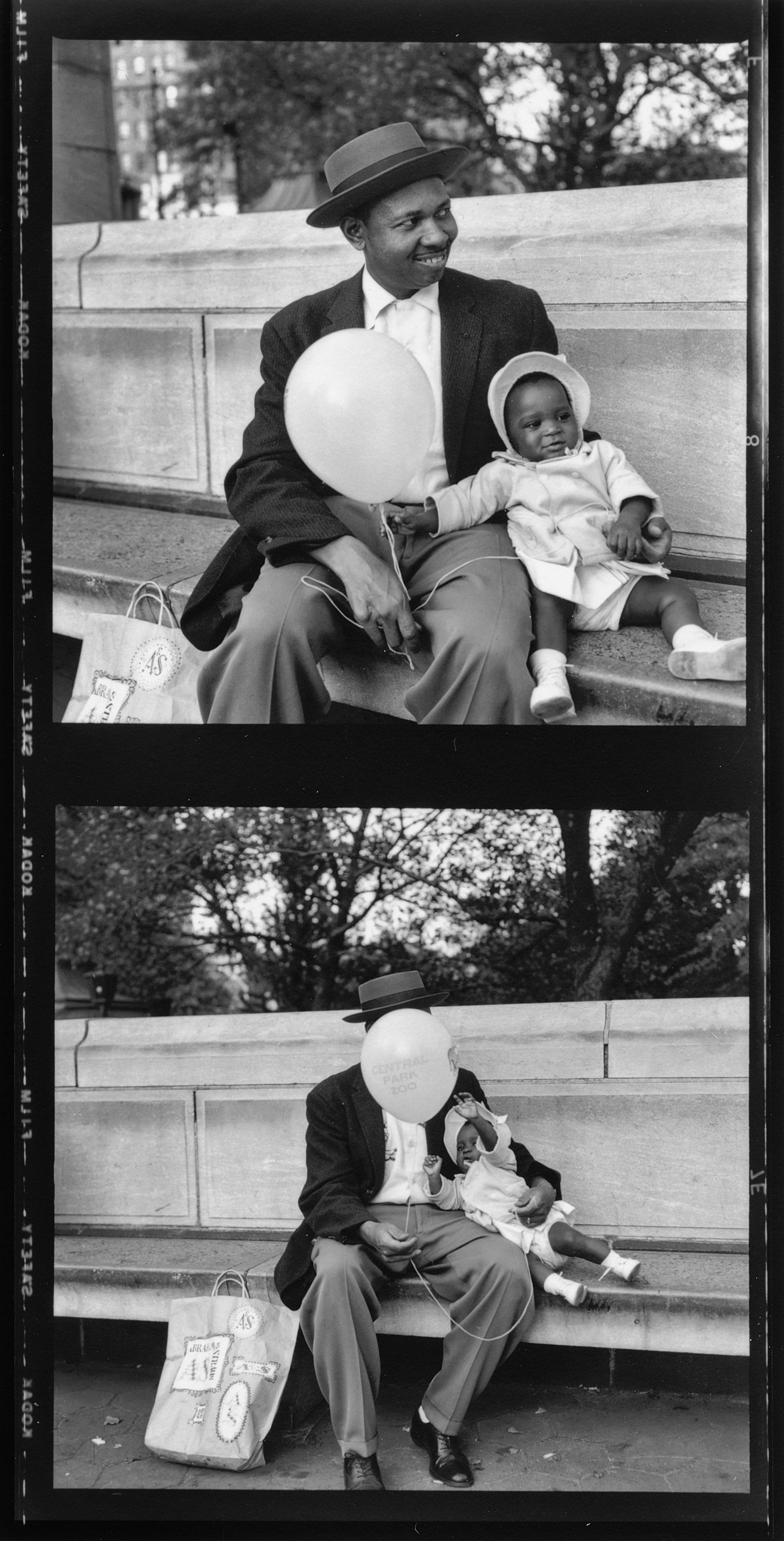

The streets became a muse for Maier, as she often snapped candid photographs of people. Many of her subjects were people on the margins of society who weren’t usually photographed and of whom images were rarely published.

Despite her meticulous efforts at composition, Maier rarely developed her own film. Fotografiska experts say that’s likely due to her fierce desire for privacy combined with a lack of stability in her career and finances. Even so, she didn’t destroy her work as some artists do. Instead, she placed undeveloped, unprinted work in storage with her other belongings in the early 2000s, when she moved between living in a small studio apartment to being unhoused. Due to unpaid rental fees, the negatives were auctioned off by the storage company in 2007, and that’s when John Maloof came across them.

Our aim was to put her name into the history of photography.

Maloof was looking for images for a book project and didn’t find anything in Maier’s collection that would work. But, even as a non-photographer, he could tell there was something technically sophisticated about the photos. He shared them online in a Flickr group called Hardcore Street Photography. Though the group can tend to be quite critical and even surly about photography, there was unanimous approval and awe over Maier’s images.

Eventually, Maloof shared the photos with galleries, many of whom rejected the works. He finally began working closely with gallery owner Howard Greenberg as well as Anne Morin, the director of diChroma Photography who curated this show.

Morin had the difficult task of narrowing down thousands of photos to select 230, as she explained at an opening event for the exhibition. She proceeded like “a surgeon,” carefully considering each image.

“We will pay tribute to a woman who is an amateur photographer,” she said. “Our aim was to put her name into the history of photography.”

Now, thanks to a fellow artist who saw something in the negatives, Maier’s name is indeed etched into the history of the medium. Her work attracts ardent fans worldwide, as does her mysterious story.

“I’ve never experienced anything close to the Vivian Maier phenomenon,” Greenberg said. “People literally from all over the world began to flock to this work. … There’s something about Vivian Maier that allows people inside her.”

There’s something about Vivian Maier that allows people inside her.

Despite the photos dating back several decades, they have a contemporary resonance, Morin notes. Maier’s creative selfies, in particular, speak to today’s questions about identity.

In addition to still photos, the artist also shot films, several of which you’ll see at Fotografiska. These moving images allow us a sense of how Maier moved her eyes to create imagery.

Though she was self-taught, Maier collected several books on photography and may have learned from her mother’s friend, who was a commercial portrait photographer. Even so, Maloof isn’t sure she would’ve handled criticism well had she tried to debut her work in her time. And he’s not sure she’d even be happy about the exhibition itself.

“Knowing how meticulous she was, there’s going to be a lot that I did wrong. … But we’re trying to do our best to show her work and respect her work,” he said. “I don’t know if she would want the criticism or the fame or us talking about her. I don’t know, maybe she would love it.”

We’re trying to do our best to show her work and respect her work.

For Maier, photography was a place to be free.

“When society erased you all the time, maybe you have to find a place to find yourself,” Morin said. “This is why I think she’s so popular. She’s no one but she’s each one of you. Each one of you has your own Vivian Maier.”