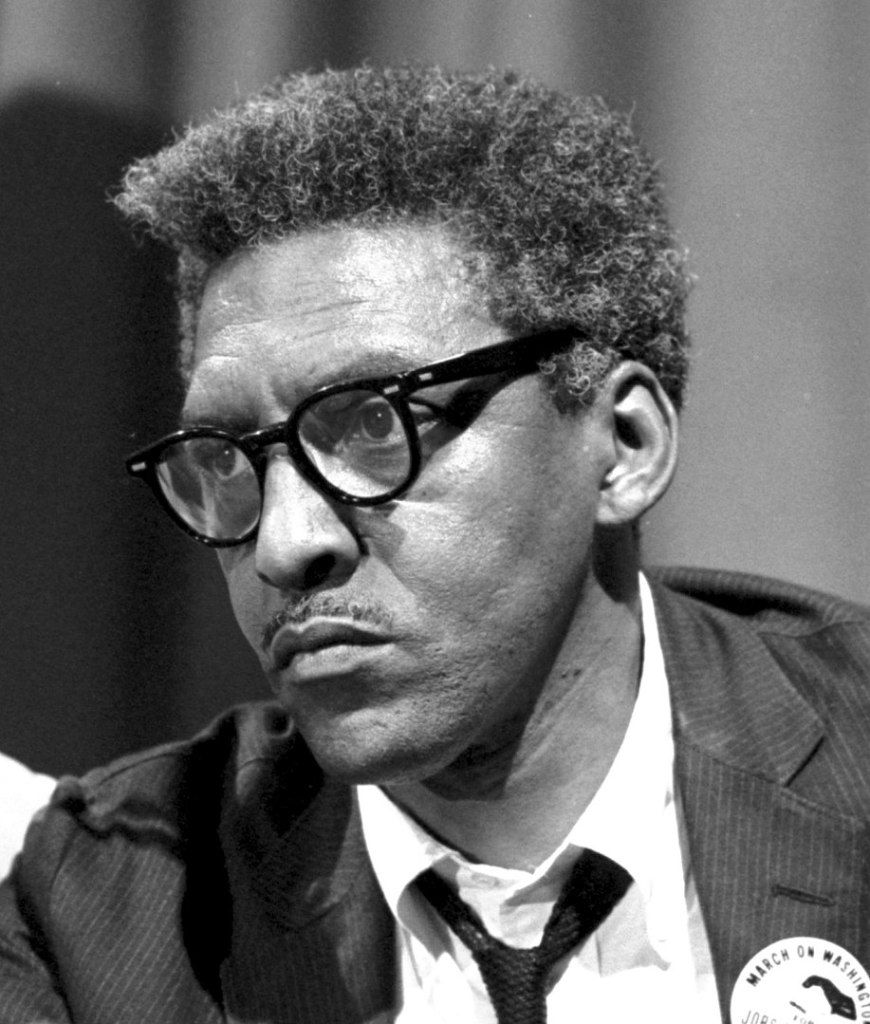

Herb Boyd: A Lifetime of Activism, Writing, and Legacy

Herb Boyd, a stalwart of American journalism, education, and activism, has spent his life elevating the narratives of the African American community. Born on November 1, 1938, in Birmingham, Alabama, Boyd’s journey led him from the turbulent racial tensions of Detroit, Michigan, to becoming a celebrated figure in academia and writing.

His life is a testament to the indomitable spirit of a generation that stood up for civil rights and social change. Further, his connection to Malcolm X, a transformative leader, shaped his path early on. In a riveting interview inside the National Newspaper Publishers Association’s (NNPA) headquarters in Washington, Boyd discussed his life and career, which include authoring 30 books but, perhaps most importantly, fighting for freedom, justice, and equality.

“I call myself a Triple-A man. Not the automobile club, but activist, academic, and author,” Boyd said while inside the NNPA’s sprawling studios filming an episode of the PBS-TV and PBS-World show, The Chavis Chronicles. “The activist came first, and that put me in the streets and in contact with many vibrant leaders,” he recalled.

While not precisely a “Johnny Come Lately,” Boyd was in lockstep with other activists. But one has always touched him more deeply than any of the others. “Malcolm is my centerpiece; my activism grew out of him,” Boyd asserted.

It was in the early 1960s that Boyd met Malcolm X and attended one of his lectures at the Detroit Temple No. 1. He said the experience left an indelible mark on him, igniting his passion for activism. Malcolm’s emphasis on education led Boyd to enroll at Wayne State University, aligning his academic pursuits with his activist ideals.

Boyd’s leadership during Detroit’s activism-rich period of the 1960s set the stage for his subsequent contributions to academia and journalism. He said the parallel rhythms of Detroit and Harlem, both significant hubs of African American culture and political engagement, deeply resonated.

“These cities became the crucibles in which my ideals took shape,” Boyd insisted. A columnist for the New York Amsterdam News, Boyd’s work includes a prolific collection of books that delve into African American history, culture, and civil rights struggles.

Titles like “Autobiography of a People,” “Jazz Space Detroit,” and “African History for Beginners” stand as monuments to his dedication to preserving and amplifying the stories of the marginalized. Writing, for Boyd, is a form of activism – a way to give voice to those who lived through history and to expose the injustices that must be confronted.

Throughout his career, Boyd has garnered numerous awards and honors, including the American Book Award in collaboration with Robert Allen and several first-place awards from the New York Association of Black Journalists.

“Our history is a testament to our resilience,” Boyd stated. “From the horrors of slavery to the civil rights movement, African Americans have never wavered in their pursuit of progress. Our challenges today require unity and a commitment to healing and progress. Just as the 1960s were a vital period, we’re still grappling with understanding that era’s impact and lessons. The path forward involves learning from history, bridging divisions, and continuing the fight for justice with hope and determination.”

Watch Boyd and others this fall on The Chavis Chronicles on PBS.

The post Herb Boyd: A Lifetime of Activism, Writing, and Legacy appeared first on New York Amsterdam News.