Stage is set for another increase to rent stabilized units

Two empty chairs sat stage left by the time New York City’s Rent Guidelines Board (NYC RGB) issued a preliminary vote allowing landlords to raise rents on rent-stabilized residential units this past Tuesday. The initial hikes were initially locked to a range of 2 to 4.5% for one-year leases and 4 to 6.5% for two-year leases beginning in October. A final vote on June 17 will determine the exact percentage for rent increases.

The vacant seats were assigned to the two tenant representatives on the board, Adán Soltren and Genesis Aquino, who walked off in protest given the seemingly inevitable rent hike despite mounting evidence of financial hardship that rent stabilized tenants already faced. They abstained from the preliminary vote, which went 5-2 in favor of the agreed upon increase; the two nays came from the owner representatives who argued the rent hike range was not high enough.

The move from the board affects nearly one million households protected by the Rent Stabilization Law, which set a legal limit to how much property owners can charge for qualifying apartments, typically those in pre-1974 buildings with six or more units. The board determines the exact limit.

The NYC RGB’s formation came as the actual Rent Stabilization Law passed in 1969, giving the sitting mayor authority to appoint nine members—five from the general public, two representing tenants, and two representing property owners—to the board. The members are tasked with convening between March to June to review housing affordability standards for both renters and expenses for landlords, culminating in a preliminary vote with a final vote to follow.

But the ultimate rent increase the NYC RGB agrees upon is almost guaranteed to stem from the initial range in the first vote, according to Soltren, who spoke to the Amsterdam News on the morning of the vote. In fact, Soltren said, there was a dispute among the board about whether they could even legally deviate outside the preliminary vote’s scope.

“You’re not voting on a specific number necessarily as to what the upward or downward adjustment would be,” he said. “You’re saying what the range would be so that for the number in the final vote with land somewhere in [that] range…certainly tonight’s vote is going to set the goalposts as to what the final vote will yield.”

To be clear, the NYC RGB does not specifically vote on how much to raise rents, but whether the city should increase them at all. It can even decide on a rent rollback to reduce costs. Yet Soltren, who also works as a supervising attorney for the Legal Aid Society, pointed out the two could be conflated given the board’s recurring decision to raise rents despite data—which informs the vote—pointing to historical financial strains on tenants.

The rent guideline board’s reports found median rents last year for rent-stabilized households made up around 28.8% of its income, and broadly reported a significant increase in non-payments and residential evictions. Homelessness within city shelters also increased, even when the newly-arrived asylum seekers were not accounted for. And under 1% of rent stabilized units, which make up 41% of rentals in 2023, remained empty.

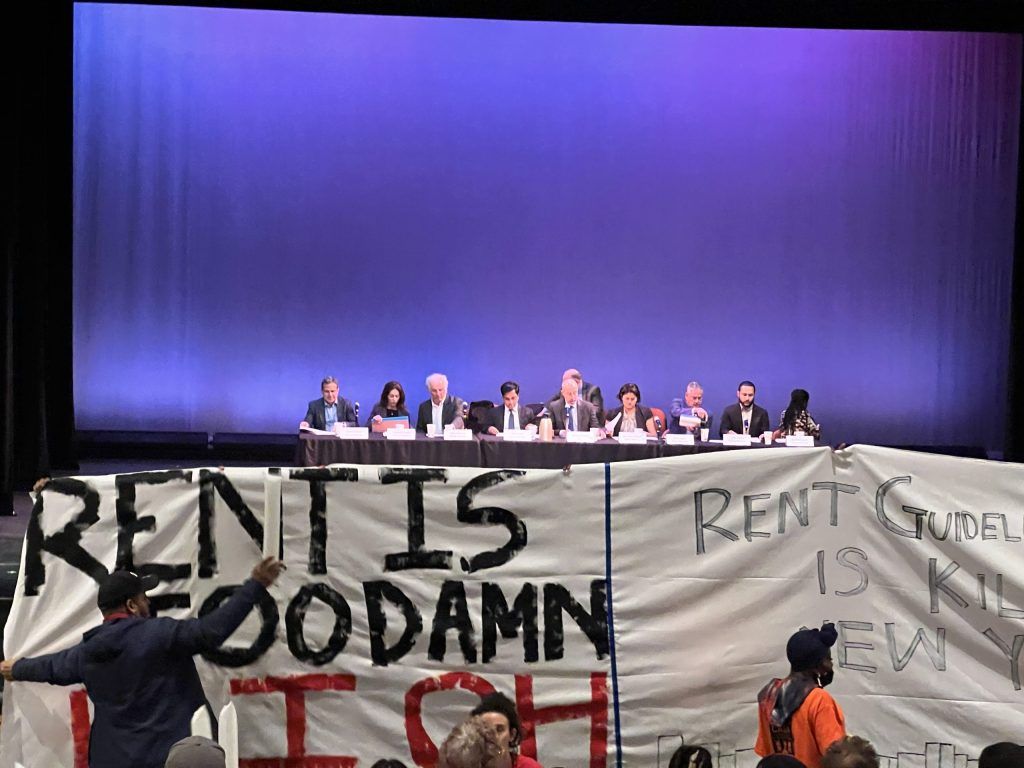

Last year, protesters led by several progressive city council members, including Brooklyn’s Chi Ossé, took over the preliminary vote stage at Cooper Union to vocally advocate against rent increases. But a 2 to 5% increase for one-year rentals and a 4 to 7% increase for two-year rentals were agreed upon anyway. A 3% increase for one-year rentals was ultimately agreed upon.

This time around, the board proceedings were similarly drowned out by protesters, whose boos and “shame” chants paired with orange thunderstix rivaled those of the Knicks playoff game across the East River. They only paused to cheer on Soltren and Aquino during their remarks and subsequent vote of “no confidence” in the board and the Adams administration.

“Rent stabilization has always served more people of color than market rate apartments,” Soltren said in his remarks. “In 2023 alone, 71% of the rent-stabilized households are headed by people of color. Despite the massive displacement of Black New Yorkers in the last two decades due to gentrification and unaffordability, Black New Yorkers still comprise 23% of the rent stabilized housing stock.

“What message are you sending to Black and brown New Yorkers when this administration and this board are calling for a third increase in three years that would likely total about 10% or more?”

After the preliminary vote, Soltren said he cited data from the most recent New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey (NYCHVS) conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. He will still need to sit on several upcoming public board meetings before the final vote, he said. After his walk-off, he is unsure how those convenings will shake out.

Civil rights attorney Robert Desir, who works at Legal Aid Society with Soltren, pointed to rent-stabilized housing as key to keeping longtime residents in majority Black and brown communities. He says fair market housing, which is not stabilized, is often out of reach for such renters, preventing them from remaining in the neighborhood if a rent increase leads to eviction over non-payment. Median rent for a rent stabilized unit was $1,500 a month last year, according to the NYCHVS. Comparatively, the median fair market rental asked for $2,000.

“Part of the rent stabilization system serves a good purpose preventing these runaway rents that result in displacement,” Desir said. “And where that’s not guarded, people fall behind, unable to afford the rent and are evicted, [meaning] those folks don’t stand a good chance to be able to stay in that neighborhood, particularly in Harlem. We’ve seen how that area has undergone significant change in the last couple of decades, and [it is] still happening.”

One protester, Ann Marie Grant, says she attended to support her fellow renters despite living in NYCHA rather than a rent stabilized unit because she fears New York City will be only for the ultrawealthy if middle-class and low-income families can’t afford rent. She says she’s seeing segregation play out in real time in her neighborhood of East Harlem due to cost of living increases and gentrification.

“I see more of my neighbors leaving and new faces taking over,” Grant said. “Gentrification is there and it’s not right. As I said, everybody should be allowed to live together, it’s not about Black versus white.”

But real estate developer Joshua Brown says “mom-and-pop” Black property owners with rent-stabilized units like himself are feeling the squeeze that come from high repair costs. While he says those issues need to be addressed by tweaking legislation, the Brookynite says a higher rent increase would help him recoup the roughly $70,000 needed to fix up his building in Bed-Stuy. Brown adds that without those costs, he would not need to raise rent lockstep with the NYC RGB’s increase cap.

“There is an incentive to keep someone who has been there a long time paying your rent on time to not raise their price just so you could possibly get a new one who could flake out within one year or two years,” he said. “However, there are root causes, there’s no incentive to do it now…what this does sadly is incentivize owners [and] developers to just keep the building vacant so that they can fully renovate the building and now you turn all these rent stabilized units into market rate units [through] something that’s called a substantial rehab…so essentially, it’s taking rent stabilized units off the market.”

The Rent Stabilization Law itself recently weathered several legal challenges, including in a case heard by the U.S. Supreme Court. In March, Mayor Eric Adams signed an extension into law, maintaining rent stabilization in the city until at least April 27. One of those organizations challenging the law, the Community Housing Improvement Program (CHIP), also objected to the preliminary vote for not raising the range high enough.

“It should not solely be the responsibility of the RGB to keep these buildings solvent,” said CHIP Executive Director Jay Martin in a statement. “Elected officials need to find ways to reduce the costs of operating housing and provide more financial assistance to vulnerable tenants. But until that happens, the RGB is faced with the Herculean task of protecting this housing stock and must step up to make the unpopular decision to increase rents.”

Mayor Adams also responded to the vote, fearing the range’s two-year cap could seriously hurt renters, but advocated for a middle ground.

“Tenants are feeling the squeeze of a decades-long affordability crisis, which has been accelerated by restrictive zoning laws and inadequate tools that have made it harder and harder to build housing,” he said in an emailed statement. “Our team is taking a close look at the preliminary ranges voted on by the Rent Guidelines Board this evening and while the Board has the challenging task of striking a balance between protecting tenants from infeasible rent increases and ensuring property owners can maintain their buildings as costs continue to rise, I must be clear that a 6.5 percent increase goes far beyond what is reasonable to ask tenants to take on at this time.”

Tandy Lau is a Report for America corps member and writes about public safety for the Amsterdam News. Your donation to match our RFA grant helps keep him writing stories like this one; please consider making a tax-deductible gift of any amount today by visiting https://bit.ly/amnews1.

The post Stage is set for another increase to rent stabilized units appeared first on New York Amsterdam News.